It’s pretty difficult to pick on one of the many dishonesties that flew around the Tory leadership campaign. The more idiotic concerned EU Brexit – a bad idea made much worse by the layers of lies laid across it. But an old friend raised his head, with that appealing combination – ideology pretending to be science. The bloody Laffer curve, now called ‘boosterism’: Boris Johnson thinks his proposed tax cuts won’t reduce government receipts. He says it, and Trump agrees.

I guess you’ll have heard of the idea that if we cut tax rates, the government will actually raise more tax revenue, because it will increase the willingness to work harder (and reduce the incentive to engage in elaborate tax avoidance measures). The Laffer curve comes from a back-of-the-envelope drawing by Arthur Laffer himself (actually, back of a napkin). You start with a graph that has tax rates, 0-100% on one axis and tax yield, say 0-100% of GNP (or sums of money), on the other. Your line starts with a 0% tax rate, which raises no tax (obviously). Increase the tax rate, and you raise more tax. Up shoots the line. However, it can’t go on forever. Charging 100% tax will raise virtually no tax at all: why should anyone work or provide products for free ? Just look at what happened when a poorly designed tax change meant doctors were being asked to work for nothing. So there must be a turning point at which increasing tax rates actually reduces the money government gets, where the line linking rates to yield begins to flatten, and then turns downwards. And if we are at that level, reducing the percentage tax rate will actually boost the Treasury’s receipts.

It’s superficially appealing. Like the left’s view that modern monetary theory, or catching multinationals, or both, mean we can spend what we like on public services, it offers the attractive option of spending more without paying more. But what did your old Dad tell you about things that sound to be good to be true ? Yep, this is one of them. Because:

- the theory assumes that people have the ability to choose to work harder – more hours, I guess – for more pay. It would be interesting to know for how many people this is true. Certainly not the vast bulk of employees. Your police officer, nurse, road-mender, assembly line worker, bank clerk and so on can’t decide to work more hours. They work what is in their contract. They may welcome some extra take-home pay, but they won’t be filling the government’s coffers.

The subsidiary argument – that people in these positions will work harder to get a promotion or upgrade if the rewards are greater – is even flakier. A firm may gain from its employees crawling over each other on the way to the top, but no extra tax will come from people working harder at a given grade or salary. Promotions are rarely available, and if person A gets it, person B won’t. The tax-take will be unaffected by who pays it. And experience suggests promotion seeking behaviour is, hmm, sometimes less than optimal for output and the real economy. - Self-employed people, however, can sometimes work longer hours or more intensively. Many of them, of course, are already eager for more work. They would like more clients right now, and this is unaffected by tax rates. It is also possible that tax cuts could make them work less hard, as a hairdresser or taxi driver can make their target income, the income needed to keep the family going, with fewer hours of work. In the jargon of economists, leisure becomes less costly, and less costly things are consumed in larger amounts. But work becomes more lucrative , so how does it balance out ? Research on taxi-drivers in USA suggested there is a modest increase in hours offered, but you then get into arguments about elasticity of supply. Will a 5% tax cut release 5% more hourly earnings ? If its less, then the whole things doesn’t work.

It’s sometimes claimed that a UK tax cut on top earners, from 50% to 45%, by the incoming 2010 Conservative administration raised receipts. This particular rabbit has been run down its burrow. What happened was this: when the lower taxation rate was announced, financiers deferred their bonuses till the following tax year, when the reduced rate would come into effect. - Much tax is not income tax. Laffer considerations just don’t apply to things like Council Tax. For some – airplane tax, insurance tax, tourist tax – it’s hard to believe there is a disincentive effect. For others – fuel tax, alcohol, tobacco – the effects of tax rises are known and factored already into government decisions. In some cases – like the sugary drinks proposals – we actively want a disincentive effect. In passing, in the remorselessly logical world of the right wing economist, indirect taxes like these should have the same disincentive effect (if one exists) as income tax. An additional £100 of work that is taxed at 20% would add no less to your wealth than would an additional £100 with no income tax that has to buy goods taxed at 20%.

- A Laffer inspired tax cut would need to know accurately where the curve turns. The UK’s 98% tax on investment income in the 1970s was indeed an invitation to evasion, but that doesn’t mean that any reduction will be profitable. The accepted estimate by most economists for the turning point is around 70%. Currently, no western income tax rate for the common worker comes anywhere near that.

- Effects on tax avoidance are assumed by Laffer fans to be a strong part of their argument. Others are not so sure. Here’s Wikipedia: Furthermore, the Laffer curve does not take explicitly into account the nature of the tax avoidance taking place. It is possible that if all producers are endowed with two survival factors in the market (ability to produce efficiently and ability to avoid tax), then the revenues raised under tax avoidance can be greater than without avoidance, and thus the Laffer curve maximum is found to be farther right than thought. The reason for this result is that if producers with low productive abilities (high production costs) tend to have strong avoidance abilities as well, a uniform tax on producers actually becomes a tax that discriminates on the ability to pay

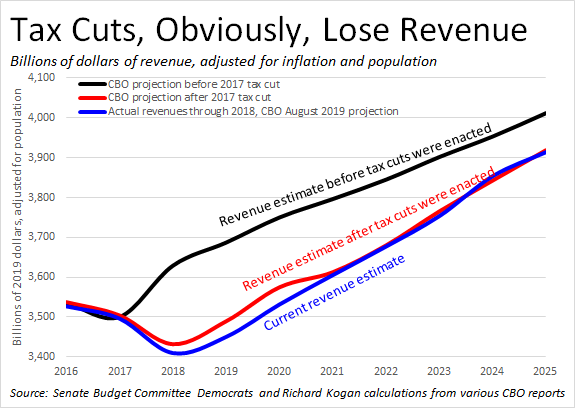

The killer point is that tax cuts for incentive have been tried, and have failed. Reagan tried it, and the budget deficit soared. Trump is trying it, buoyed by the same predictions – “some proponents … even argued that its macroeconomic effects would be so large that the bill would actually increase revenues” – but, sadly, punished by the same result. The latest predictable report can be found here. The state of Kansas provides perhaps the most egregious case-study: its Republican legislators cut its taxes in 2012, promising ‘an adrenaline shot in the arm for the economy’[1]. Laffer himself assured them they would make more money that way. They didn’t: of course they didn’t. The result was close to catastrophe. Tax receipts fell $700m in the first year. Road repairs stalled. Health care in rural areas declined. The courts ruled that the cuts to the schools system (some had to close one day a week, and subsidies to poorer areas were abolished) were alarming enough to be unconstitutional (the governor promptly tried to defund courts ruling on such issues). This makes the original mistake the more deeply worrying. Instead of saying “we got it wrong – let’s return to the original tax base”, the right will say “the budget is out of balance – we can no longer afford the current level of public services.” First in line is usually social benefits (2): last will be defence. It will happen under Trump: watch this space.

(Added January 2020:

So, an idea that doesn’t work, and will worsen public finances. I’m far from the only person saying this – see another blog, by Richard Murphy, a tax expert that the BBC invited to their studios but decided not to use. It’s truly striking how unalarmed conservatives are by all this. Centrist or radical government causing the same deficit by more generous social benefits, better schools and transport, shorter hospital waiting lists would get both barrels from party and press about fiscal irresponsibility. But deficits caused by tax cuts for the rich, not so much.

[1] An independent study showed that higher taxed districts had been growing faster than lower taxed districts in the previous 8 years. But the Kansas Republicans, like Michael Gove, had had enough of experts.

(2) Ironically, the highest disincentive taxation in our system is on social security payments. People on Universal Credit who work and don’t get or earn above the work allowance get their benefit cut when they earn more. Effectively, they pay tax on every extra £1 they earn of 55% to 76% (higher in some cases) in other words earn £1 keep 24p to 45p.