This is a different kind of blog from me – no economics, no education policy, none of the wise stuff that has kept the site going for 25 years. It’s a travelogue, but a very special travelogue. I have a grandson who is a history enthusiast and I’ve long promised him that we’ll do a tour of World War 1 battlefields. He’s off to university in a few weeks, so it was now or never.

The outline

What we planned was a visit to the two main sites of action for British and Empire forces between 1914 and 1918. One was Flanders, with the Ypres Salient and Passchendaele at the centre of the fighting. The other was, inevitably, the Somme, with the ghastly fighting of July 1916 just one episode in a long and bloody encounter. I say “Empire” because that was the term then used, before being replaced by “Commonwealth”; and the reason it needs to be included is the vast numbers of Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, Indian and South African soldiers that were involved.

In Flanders, we were in the Ypres Salient, a wedge of land that jutted into the German lines, providing opportunities to be shelled from all sides, especially as the Germans occupied higher ground. Flanders resembles Lincolnshire – flat ground, prosperous agriculture, but a high water table that meant that any shelter dug into the ground became water-logged. The Somme was 100km further south – again, agricultural land but this time with rolling countryside, hills and forests – Gloucestershire perhaps, Rutland or Northamptonshire.

Day One – Thursday, 7th August 2025. Poperinge and Ypres

We crossed to France using the Channel Tunnel. The terminus is maybe an hour’s motorway drive from London, the crossing taking 35 minutes, and (as the customs and passport formalities are done before boarding), we drove straight from the tunnel’s rail platform onto the main autoroute out of Calais. As the British army was allocated the northern section of the trenches that stretched from Switzerland to the Channel, its battlefields and cemeteries are easy to reach. With today’s motorways, we were never more than 90 minutes from the coast. Soon we were over the (invisible) border and into Belgium.

Poperinge was our first stop. It’s a medium sized Belgian town that was one of the only ones to escape German occupation. Placed just behind the front lines, it was where British and Commonwealth troops detrained after crossing the Channel. We grabbed a late breakfast and started to explore.

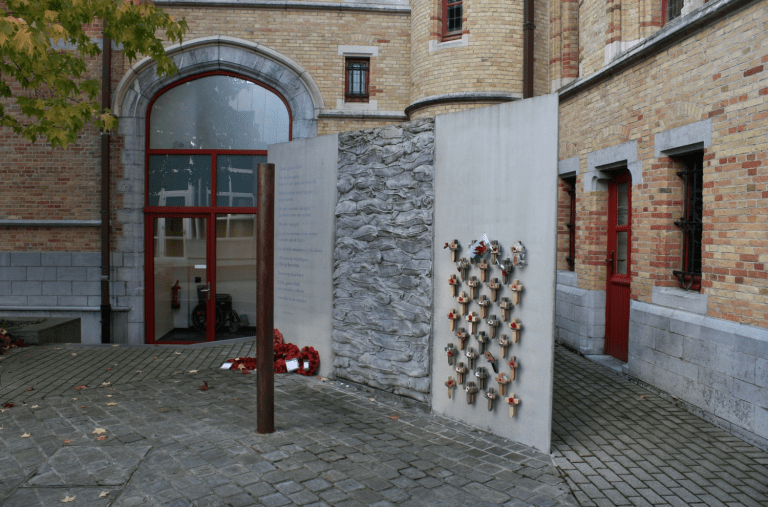

The first historical site was one of the grimmest – the condemned cell for soldiers about to be shot for cowardice. It’s an undistinguished stone room, tucked next to the Town Hall, no bigger than most people’s bedrooms. There is some graffiti on the walls, the odd crucifix or name: for some soldiers, it was just the cell for drunkenness. Those suffering the severest penalty – their paperwork now displayed as superior officers countersigned the death penalty – “I see no reason to change this verdict” – had maybe ten metres to walk to a steel post in the neighbouring courtyard. There’s a good site with further information here.

Walking back to our car, we passed Toc H. This was a soldiers social club, set up by a clergyman to provide an alternative to the bars and brothels that had shot up for the thousands of young men. A friend tells me the only rule was that you leave your military rank at the door.

We then drove to the second biggest cemetery in the Ypres Salient, which is quite a claim as there are 174 cemeteries in that battlefield area. This was the Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery, maybe a ten minute drive from Poperinge town itself. The reason it was such a large cemetery was that it was next to the biggest hospital in the Ypres Salient. Even if only three per cent of those admitted died there, that was enough to provide 10,000 graves. A neat modern visitor centre lies alongside the cemetery, and you can make out the railway lines that brought casualties to and away from the hospital. One room of the visitor centre is devoted to airmen of the Royal Flying Corps: casualties were very high there, and, it seemed, often as a result of mechanical failures or poor training rather than enemy action.

Ypres We drove off towards Ypres maybe 20 minutes away, finding the lovely Albion Hotel just off the town centre. The Grote Markt is that centre – an open market square made up of traditional Dutch style buildings housing shops next to the magnificent Cloth Hall, originally built between 1200 and 1300. It was utterly destroyed during WW1, and has been completely restored, opening again in the 1960s, and now housing a fine museum full of interactive elements. Testimony from locals and nurses as well as soldiers competes a sombre experience. Give yourself a couple of hours at least.

We’d got up at 5.00 am to leave London, so were pretty tired and had a lie down in the hotel, dining on a designer burger later and moving to the Menin Gate. This is a monument built into the city walls of Ypres, bearing the 55,000 names of those with no known grave (some tourist sites say it will be shut till 2027 for renovations, but they have now been completed). Each evening there is a brief service of remembrance there, arranged and supported by local Belgian people, and attended by visitors from all over the world. The place is packed. A bugler plays The Last Post, a brief poem is read, and wreaths are placed on the memorial. When we were there, this task was done by Boy Scouts from Chorlton in Manchester, and by Canadian Girl Scouts. Matters are ended by the bugler playing Reveille.

We dropped into the Commonwealth War Graves Commission office next to the Menin Gate. Milo and I knew of my relative buried further south, but we didn’t know if there were casualties on his father’s side. My son-in-law’s name is uncommon and that made it easier to discover Private John Leesley 241498, killed on 18 October 1917 – the only military casualty Leesley out of 1.7m dead[1]. That’ll be a grave more difficult to visit, though: the citation says he is remembered with honour in the Baghdad North Gate Cemetery.

Last stop was a local pub. Were it not for WW1, Ypres might be best known for its beers – lying in wait for the unwary on the bar menu at strengths up to 10% and beyond. The fields around, amid the maize and potatoes, often feature hop poles to feed that local industry. Ypres is now Flemish speaking – properly called Ieper. I speak moderate French, but local people were happier speaking English than French.

Day Two – Friday, 8th August 2025 Ypres

We slept well, grabbed a decent hotel breakfast, and then met our guide for the day’s tour outside the hotel. Kimberley Wright was terrific – from the Wirral, now transplanted to Flanders to be a battlefield guide. We piled into a Mercedes people-carrier with an American father and son from Oregon, a Dutch and a Belgian couple.

First stop was the Essex Farm cemetery. It was a poignant place to start. After a brief outline of the war’s beginnings, we walked over to the grave of Valentine Strudwick, at 15, the British Army’s youngest casualty. Boys this age enlisting was not uncommon, but this death caused an outcry by parents for their sons to be found and returned to the UK. A search was made, and eligible boy soldiers were told they could return without penalty. Many, however, resisted, feeling it would be letting down their comrades to go back home.

The Essex Farm cemetery is next to the Ypres Canal, which was the front line for a while, and the dressing station for wounded troops. This was in concrete, sunken to provide cover from enemy fire, dark and damp now but you can look inside. It provided first stage medical help for casualties – some hopeless, packed away from sight, given morphine, perhaps accompanied by a nurse in his dying moments, perhaps not. Others were easily patched up, and sent back, whilst the seriously injured but saveable saw their wounds dressed and cleaned before they were sent back to a hospital behind the lines or in Britain. Our guide spoke of the terrible wounds that were caused by modern artillery, often creating the appalling facial injuries that led to advances in plastic surgery. One man’s face was so disfigured that his wife divorced him: her disgusted friend carried on visiting, and eventually married him[2].

The doctor in charge of the dressing station at Essex Farm was a Canadian – John McCrae. He was moved by the death of a close friend to write the now famous poem “In Flanders Fields” that has led to the poppy becoming the emblem of remembrance.

In Flanders’ fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place: and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders’ fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe;

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high,

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders’ Fields.

Notice that it isn’t a pacifist poem, unlike the work of Owen, Graves, Rosenberg or Sassoon. We are told that we must carry on with the fighting or betray the valour of the dead, Maybe McCrae changed his mind on that: he is alleged to have become more fractious and depressed, his final diary entry in January 1918 saying “I keep working, but they keep dying” before he himself died of pneumonia a week later. The footpath from the canal to the casualty station is named McCraepad – McCrae Path.

We climbed back into our minibus, and drove to the Yorkshire Trench, discovered in the 1960s as a new industrial estate was built. The remains of 155 French, German and Yorkshire soldiers were found as well: even today, between thirty and forty bodies are found in farms and fields around Ypres each year. With Flanders’ high water table, the trench and dug-outs were completely full of water, but this enabled the preservation of many artefacts – timber trench-frames, bunks, blankets, razors – even the pump was found to be in working order. The subterranean areas are not accessible, but their outline is traced above ground by gravel paths that indicate the size of the various facilities beneath.

The German cemetery at Langemark was next, and Milo found it a highlight. The design was, if such was possible, more sombre than the Commonwealth graves – black stone, level with the grass, no flowers or shrubs, and a large uneven area holding, it is said, 20,000 bodies. The area is subject to myth making – ‘birds never sing there’ (they do), German bodies were buried upright (they weren’t) and such. What is true is that this area is the site of the Kindermord – the ‘massacre of the children’ – German student volunteers who joined up eagerly in 1914[3], and were mown down by their first encounter with the experienced professional soldiery of the British Expeditionary Force. After German forces overran the area in 1940, Adolf Hitler came to this site to give an oration, claiming (it is said) that he was there. He had a genuine war record, but it wasn’t here.

The next location that Kim took us to was the St Julien Memorial, now more commonly referred to after the statue that marks it – The Brooding Soldier. This was the site of the first poison gas attack in the war on April 22nd 1915. The Germans released the gas when the wind was blowing from their lines, causing French colonial troops to break and retreat, leaving a 5 mile hole in the Allied defences.

The Germans were slow to realise the success of their new tactic, enabling French and Canadian forces to come forward to fill the gap. In the 48 crucial hours that they held the line, 6,035 Canadians – or one man in every three who went into battle – became casualties; of that number, approximately 2,000 (or one man in every nine) were killed. The parkland around the statue features Canadian shrubs, one of which – a low green bush – ghoulishly mimics the look of chlorine gas creeping over the ground.

Tyne Cot We finished our tour at the largest cemetery for Commonwealth forces in the world, Tyne Cot. Named by soldiers from Northumbria because of the resemblance of pill-boxes to workers’ cottages on Tyneside, it contains more than 10,000 graves. Many of these died in the Third Battle of Ypres, known more commonly nowadays as Passchendaele. The cemetery is, like all the others, beautifully kept. Being located on higher ground, our guide was able to point to some wind turbines maybe five miles away, where the advance started in July 1917: we could walk there in a couple of hours, whereas the soldiers took five months to gain the ground,

The minibus took us back to the hotel. It had been a terrific tour, taking us to places we would have missed, and enabling us to talk to other visitors. We were pretty tired, though, grabbed a late lunch snack, and collapsed in our hotel with a drink and a rest. I decided to look at the ‘cathedral’ – Ypres St Martin’s Church, finished 1370[4]. It’s actually no longer a cathedral, as Napoleon got together with the Pope to reorganise Belgian bishoprics, but it was an impressive building nonetheless, in the sombre Dutch style. It’s a centre of organ music, and though I missed the recent festival, organ music still played as I walked around. The most ‘distinguished’ person buried in the church was Cardinal Jansen, the originator of Jansenism. Different heresies are a mystery to me, so I looked it up. It’s a bit like Calvinism – the idea that an individual’s fate is determined not by virtuous behaviour but by the grace of God, about which you can do nothing. God, it is argued, does not grant you free will. As an atheist, I find most theistic beliefs odd, but this one is not just weird but unpleasant, a sort of religious bingo where you simply see whether your number comes up. People fought, died, were prepared to be burned and tortured for this stuff, so they were sincere enough. But reasonable, logical, sensible ? Hmmmm …

We ended the day having a great meal in a restaurant called the Captain Cook (always appealing to those of us with Middlesbrough connections). Milo had an epic calzone, I tucked into the chicken in mushroom sauce followed by the (inevitable) Belgian waffle. We fell into conversation with diners on the next table from Malton, who tipped us off about the site of the 1914 Christmas truce, maybe 15 minutes’ drive from town. That decided our first stop on Saturday.

Day Three – Saturday, 9th August 2025 Auchonvillers After a good night in our nice hotel, and an ample breakfast, we checked out. The plan today was to drive south to the Somme, another area well known for its WW1 associations. The car had charged fully overnight in the hotel car park (excellent) giving us 350 miles in the battery, no problem given the Somme was maybe 70 miles away, at most 90 minutes of leisurely French motorway driving. But we were going to take a modest diversion – of which, more anon.

First stop of the day was at Ploegsteert, or Plug Street as English soldiers called it. On Christmas Day 1914, hearing carols being sung, soldiers climbed out of trenches, exchanged gifts, and played some impromptu games of football. They also took the opportunity to collect and bury their dead.

The episode has attained mythic proportions, but it certainly happened, and is commemorated by a bronze statue in the town square of the nearest village, and a FIFA sponsored stone memorial, signed by Michel Platini, five minutes away at the actual field. A couple of French hikers obligingly took our photo. There remain some trenchworks at the memorial site, and a look around the local landscape shows cemeteries on both sides. It seems pretty clear that, after the Christmas truce, the armies on both sides reverted to business as usual.

Wanquetin We then drove over the invisible Belgium-France border towards our next destination – the grave of my great uncle, Fred Daly, known as “Sonny” in the family. He was my grandmother’s brother, and emigrated to Canada before the war started. When war broke out, he enrolled in the 28th Battalion of Canadian infantry, which was known as the North-Western as it recruited in Manitoba and other far flung provinces. He served throughout the war, being killed with 14 comrades when a German aircraft dropped a bomb on their sleeping quarters on 18th July 1918. The family legend was that he was a horseman, and was killed when he came out to calm the horses who were spooked by artillery bombardments. The truth is found in the battalion records, which are available on the internet in astonishing detail, day by day, here. You’ll notice that the battalion carried on the next day with a sports day against a neighbouring unit as if little had happened.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission keeps immaculate records, and they placed his grave at Wanquetin Community Cemetery – a small local addition to the ordinary cemetery of a modest Somme village, on the outskirts of Arras. We walked through that graveyard, full of local memorials of varying taste, some of which had notification from the local council that the grave was neglected, and would be taken over unless the Town Hall was contacted within the year. Other graves had individual names with birth years but no death date, indicating that it was a reserved spot for a family member still living locally.

The extension which makes the military cemetery is beautifully kept. The grass between the gravestones is neatly mown, and the stones themselves are set amid low growing shrubs and flowers. The grave is easy to find, as the end gravestone on each row has a reference number – Frederick Daly’s was II B 15, and lay alongside the other members of his detachment killed in the same incident. We had bought one of the little pine crosses from the Ypres Museum, written our message, and pushed it into the ground at the base of his stone. We were the only visitors to the military section. The countryside nearby was lovely, helped by glorious summer weather. The field behind the war memorial held a group of magnificent horses.

Pt Daly died in 1918. This area is better known for the 1916 Somme battle which was launched to relieve pressure on the French Army, which was being remorselessly attacked around Verdun and was suffering mutinies. The planning, however, was poor. Troops were assured that preliminary shelling would destroy the German defences, but when they rose from their trenches they found the Germans had been fore-warned, and spent the bombardment in deep shelters, ready to emerge as soon as the Commonwealth troops appeared. 10,000 British and Empire soldiers died on 1st July 1916.

Modern historians differ from the Blackadder “lions led by donkeys” view of the Somme, maintaining that it was a necessary battle, and the losses imposed on the Germans were crushing. You get the idea in this YouTube clip – but I remain of the old school, that (as one commentator out it) “gaining seven miles for 600,000 casualties cannot be claimed a success”. Not a debate to enter into here, except to say that (a) the Germans subsequently withdrew from the contested area, enabling allied troops to simply walk across the battlefield and (b) later generals like Sir John Monash combined tanks, smoke, artillery, air power – technology that was available in 1916 – in combined attacks that made great gains for a fraction of the casualties.

Ocean Villas We’d booked in for the night at a B&B run by a celebrated Englishwoman, Avril Williams, at the village of Auchonvillers, near the Beaumont Hamel battlefield. As elsewhere, the Tommies gave it a pronounceable English name, reported by the poet Edmund Blunden who used a farm building on the site as his pill-box, as “Ocean Villas”. The building that Avril has converted into such a nice B&B was once a farmhouse, and its cellars were used as a dressing station for casualties. The trench at the back of the house still exists, as does the cellar.

The other guests were British (one was a businessman who worked in Milan, and decided to bring his half-Italian son along as he drove to visit relatives in England) and most were history buffs. A couple of friends were, I guess, from the services as they joked over breakfast about having to learn Morse code. Another guest was head of history at a high school who decided to retire early and become a battlefield guide. He and his wife come out several times a year. The B&B is close to many Somme sites, so we dumped our bags and used the afternoon to visit two that were both less than five miles away. One was the Newfoundland Monument, remembering the Canadian dead of the Somme, and the other was Sheffield Memorial Park.

The Newfoundland Monument is set on the actual battlefield the Newfoundland Regiment fought over. The trenches are still there, though now grassed over amid the trees. At the centre is a mount crowned by the statue of a caribou, the badge of the regiment that fought here and suffered appalling losses. The Newfoundlanders had been told that there were insufficient men from their province to make a separate regiment so they’d be integrated into other Canadian units: they refused. There is a well-kept and modern visitor centre, which includes a photograph of the first group of families to visit the site after the end of the war.

The park is supervised by young Canadian men and women in park ranger uniforms, who are happy to guide groups, direct visitors to points of interest, or just take a photograph (see left).

Sheffield Memorial Park was the next point of interest. We drove there in ten or fifteen minutes, passing seven substantial cemeteries on the way. You get to the Sheffield Park and its three associated cemeteries up a bumpy agricultural lane. Warned that the local farmer was getting fed up with visitors blocking access for his tractors and harvesters, we tucked the car next to a cemetery wall, and walked the last 500 yards or so, past waving maize fields. The park is now wooded, though the outlines of shell holes are plain enough to see. It contains a memorial building, with a book of remembrance. By 1916, the British army was no longer made up of experienced professional soldiers, but was mostly volunteers. Amongst these were the “Pals Battalions” formed from neighbourhood groups or factory co-workers. On July 1st, by 0750, half an hour after the first soldiers had emerged from their trenches here, the attack had failed. The Accrington Pals suffered 585 casualties, the Sheffield Pals 513, the 1st Barnsley Pals 286 and the 2nd 275. The devastation this caused to small towns led to the idea of Pals Battalions being quickly abandoned.

So then it was back to an evening meal at Avril’s establishment, with guests sampling Belgian and French beers whilst we retreated back to our room and slept.

Day Four – Sunday 10th August 2025

The day started with a full English breakfast, with some of the eggs coming from the chickens that clucked their way around the estate as if they owned the place. We’d heard from other guests that the B&B had its own museum, and sure enough, our hostess showed us across the road to a converted barn that contained a treasure trove of items discovered in fields, donated, or bought from other museums. Having seen the Blackadder episode about shooting General Melchett’s favourite bird, we were interested to see a public poster warning that the penalty for shooting a carrier pigeon was £5 – £500 in today’s money, but at least not the firing squad. There was also a room of WW2 artefacts, with a complete Willys Jeep.

Thiepval Monument It was our last day in France, and we were due on the LeShuttle at 19.30, so we needed to pack some unmissables in. One was the Thiepval Monument, another enormous brick and limestone construction that commemorates those 72,000 who died with no known grave, all of whose names are to be found on the massive walls. So many died that those with common names – J Clark, W Smith and so on – have to be distinguished by their army numbers. There was a French museum nearby, but we were pretty “museumed out” by this stage, and just walked across the immaculate lawn to Sir Edwin Lutyens masterpiece. I say masterpiece. It was described by Gavin Stamp as “the greatest executed British work of monumental architecture of the twentieth century”, and the design of interlocking victory arches allow all the names to be read by visitors, but I found it overbearing, almost clumsy. As ever, if you stand on the plinth and look around the countryside, within 400 yards there is a cemetery full of young men whose grave is known.

Arras Time was catching up with us, and Milo wanted to spend some time in a normal French city, so we pulled in to Arras, which was halfway to our next destination.

Not knowing the city, I aimed for the cathedral, but that seemed dull and remote so we parked up in the massive Grand- Place. This turned out to be an impressive square, surrounded by houses and shops in what is known as the Baroque Flemish style. It does indeed look very Dutch to English eyes. We needed food – we weren’t going to be back in London till late evening – so settled down to a solid lunch – the Camembert salad was too big even for my appetites, and Milo marvelled that the waiter asked him precisely how would like his burger to be cooked. Rather than order a pudding, we decided to do some more town walking, ending up in front of the Town Hall with an emotional sculptural memorial to the dead of the 1940-44 resistance. This square was equally impressive, and came equipped with an ice cream stand that served our dessert needs.

Vimy Ridge was the last, and in many ways the most impressive, of all the memorials we visited. It stands on high ground with extensive views over the surrounding countryside (and a few coal heaps). The battle took place in 1917, and Canadian forces, working together at last, conquered the ridge that had defied many previous attempts by the Allies. One attempt was by the French Moroccan regiment, who in 1915 dislodged the Germans from the crest, but had to withdraw when reinforcements failed to arrive. They have a memorial nearby also: I’ve learned that many of these troops were in fact Senegalese, which may account for the colourfully dressed African women whose photo I took on our visit.. We’d left the car in a car park maybe 800 yards from the ridge’s edge itself. The way to the monument was clear, a straight walk across mown grassland. Milo would have preferred to approach through the battle area, where shell holes and defensive positions were still evident, and trees provided shade on a hot day. This wasn’t possible. As we got nearer the monument, that way was prevented by electric fences, and regular notices warning that the ground was still full of unexploded ordnance.

The monument itself is in magnificent white limestone, and has a much more artistic and sculptural feeling than the brick and Portland stone of Menin Gate or Thiepval. It also has an air of mourning, with a female figure prominent. As with many other monuments, the names of those with no known grave are engraved on the monument, though Wikipedia suggests that the architect protested this was not part of the original plan.

And with that, our trip came to an end. Calais was maybe an hour away, and we decided to arrive early at the tunnel to see if we could catch an earlier train, as we had when coming to France. This was a mistake. You have to arrive an hour early to embark anyway, and ‘technical difficulties’ mean that trains were an hour late, not early. In brief, we ended up spending nearly four hours at the terminal – not a disaster, but a downbeat end to a fascinating holiday. We arrived at my brother’s house in south London at 10.00 that evening, grabbed a beer and turned in.

Conclusion I was impressed by the interest that is still shown in the battlefields of WW1’s Western Front. I wondered when the sense of remembrance will wither away, but the answer is not anytime soon. Tourists still visit the sites, and the Menin Gate ceremony is positively crammed full. Many graveyards had no visitors- like Wanquetin until our arrival – but they are beautifully maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, sometimes (as at Ljissenthoek) by the descendants of the first gardeners who came across from Britain in 1919. The cemeteries are carefully signed from main roads. The larger ones have modern visitor centres, expertly staffed and free to enter like the car parking.

I said earlier that we got a bit “museummed out”, and I think had we stayed longer we would have wanted to do more battlefield walking, understanding where the forces stood and their movements. The Imperial War Museum’s London site has a trench experience which might have been a good preparation for us,

I’ll end with thanks to those involved. My brother and sister in law, Simon and Jackie, live in Eltham in South London, conveniently close to the M20 and they played host to our adventures. They could not have been kinder. The bookings of hotels and tunnel were done promptly and efficiently by James Power of Somme Battlefield Tours, who provided maps and suggested routes and tours in the battlefield areas. We could go back and follow his ideas for weeks, and still not scratch the topic. Kim was a great guide, highly recommended if you’re tempted do a similar trip in Flanders.

Main thanks go to Milo Leesley, my navigator and co-conspirator. He showed extraordinary tolerance and good humour for a 17 year old: when the American teacher on tour said “young people don’t read books these days”, he smiled quietly and returned to his well thumbed copy of “Oliver Twist”. He put up with what would be, in a weaker man, a fatal level of anecdotes from me. It’s also useful to have someone to tell you to drive on the right first thing in the morning, and operate the toll gates on French motorways. One of the motives for going was hearing a favourite song “The Face of Appalachia” by John Sebastian, about a grandfather who promises to take his grandson on a walk in the Appalachians, but never gets round to it[5]. I’m 80, and Milo is off to Leeds University next month, so, as I said earlier, we ran it close, but we did get round to it.

[1] There is a civilian casualty – John Leesley, who died in 1940 during the Second World War bombing of Sheffield. He was killed in the Hermitage Pub, where his relatives many years later gathered to celebrate a Sheffield United promotion.

[2] Another advance was the use of X-rays quickly after the wound. Marie Curie herself – with her 17 year old daughter – organised the French Red Cross X-ray unit, using lorries to carry portable equipment that could be used to help treat casualties with metal fragments

[3] Reminiscent of the scene in both versions of “All Quiet On The Western Front” featuring a university professor urging his students to join up.

[4] And (of course) utterly destroyed in WW1, rebuild to the original design in the 1920s

[5] Actually, the best version of this song is by Valerie Carter, on her utterly wonderful and totally neglected album “A Stone’s Throw Away”.